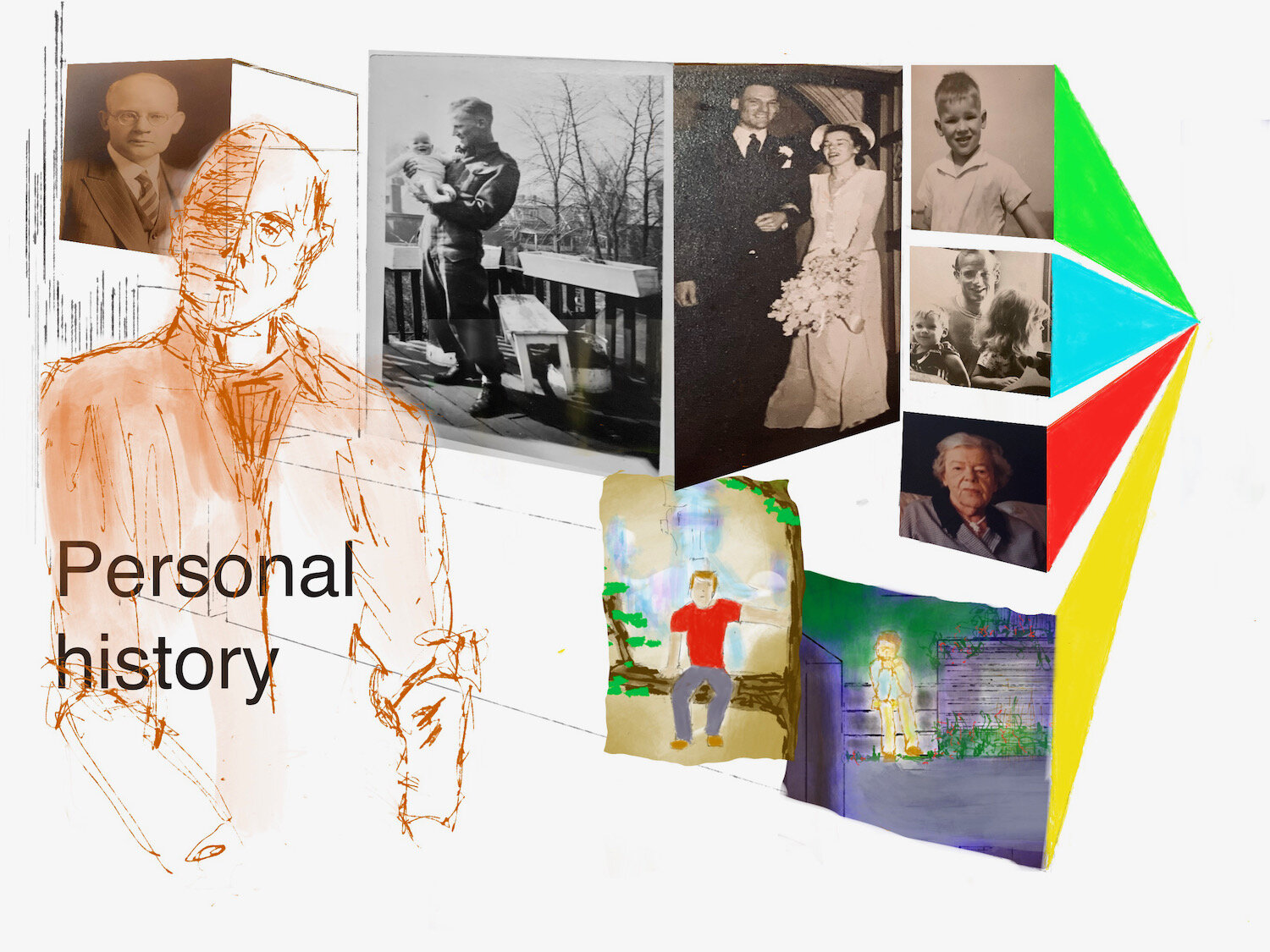

Personal History

After about fifteen drawings, I found myself creating a picture of my own: a wily old fox looking out from behind a featureless human mask, allowing himself to be seen; and the mask was held by a human hand. That’s me, I realized. Not just the fox, or the mask, or the hand: all three, together. That’s the person whom I have become.

On the final night of the course, he took us into the empty theatre, and we sat scattered across its steeply raked two hundred seats in the dim. The stage was dark. “The true playwright,” Tom told us, “gets goosebumps, just looking at the empty stage.” And that’s exactly what I was feeling: goosebumps. All these imaginary creatures, calling, waiting to be drawn into existence; all these stories, asking—demanding—to be told.

I experienced a quiet revelation last week. Quiet, but far-reaching. Writing it down makes it sound more dramatic than it was, since I’d already mostly come to terms with the separate elements of the story. But just the same, it was shocking, and it is—or should be—life-changing. I realized that I’ve wasted my life on three things: a mean-spirited and ungrateful family; a writing market that neither needs nor wants me; and a religion that rejects me and my kind.

I always wanted to draw but never could. A Christmas gift in my teens didn't help: Drawing Made Difficult, it was called. I switched to writing. And then, about three years ago, plagued by writer's block and inspired by the discovery that I could sculpt strange puppet faces, I picked up a pen and started copying photographs of birds. It was only a warm-up exercise, something to begin the day creatively, rather than sit sweating at a wordless screen….

They seemed like such a successful couple. They were liked and admired by neighbors, and acquaintance—always well-dressed, always well-mannered, Dad something of a character with his famously “booming” voice, my mother with her sudden laugh and continual empathy. They gardened; they conducted vigorous Sunday walks, sticks in hand, through fields and along riverbanks; they constantly. entertained—desserts and drinks (always drinks) on Saturday or Sunday evenings in their pleasant large living room, often before a roaring fire, everyone talking over each other, shouting louder and louder as the drinks went on into the night, my father booming over them all.

“Never say a word to your mother about her father, Jerry. She’ll cry.”

Dad delivered this warning in a hoarse stage whisper and went on to explain that my brilliant maternal grandfather—a Rhodes Scholar, Jerry—died from an angina attack while carrying a bucket of coal up the cellar stairs, shortly after losing a fortune—three hundred thousand dollars, Jerry!—in the crash of 1929.

When she moved to a nursing home in 2002, I thumbed through Flight of the Mind, the book in which she kept her cash, to be sure that no money remained in its pages. That’s when I found its hidden treasure: a single, undated typewritten page, written by her, at some point before her move to Ottawa. I’ve kept her always eccentric spelling, capitalization and punctuation….

I opened the conversation with a few broad rhetorical strokes, in which I reminded everyone of the tumultuous nature of the past year—the pandemic; the attack on the seat of US government by a mob egged on by the then president himself; the Black Lives Matter protests that seized our cities; the rise of the extremist right; our own soul-searching on the issue of systemic racism. But if I expected some artistic version of the podcasts and the hand-wringing articles that we all hear and read—I was wrong.

“How’s Wray?”

“Dad died fifteen years ago.”

“Did he?”

A reflective pause.

“Well, I certainly haven’t missed him!”

There’s a lot going on in this poem, beneath its rather conventional, hymn-like stanza form and rhyme; and the more time you spend with it, the deeper it becomes. It’s a bit too linear for my own taste, yet its mysterious power depends on that linearity: the series of questions, all unanswered, with the underlying image of the manufacturing forge. The unanswered questions drive home the single fact that God made this terrifying thing, this beautiful killing machine of flesh and blood, the tiger who inhabits the unknown “forests of the night”.